How to have better Sends with Friends

Or Intentional Skills to Climbing Improvement

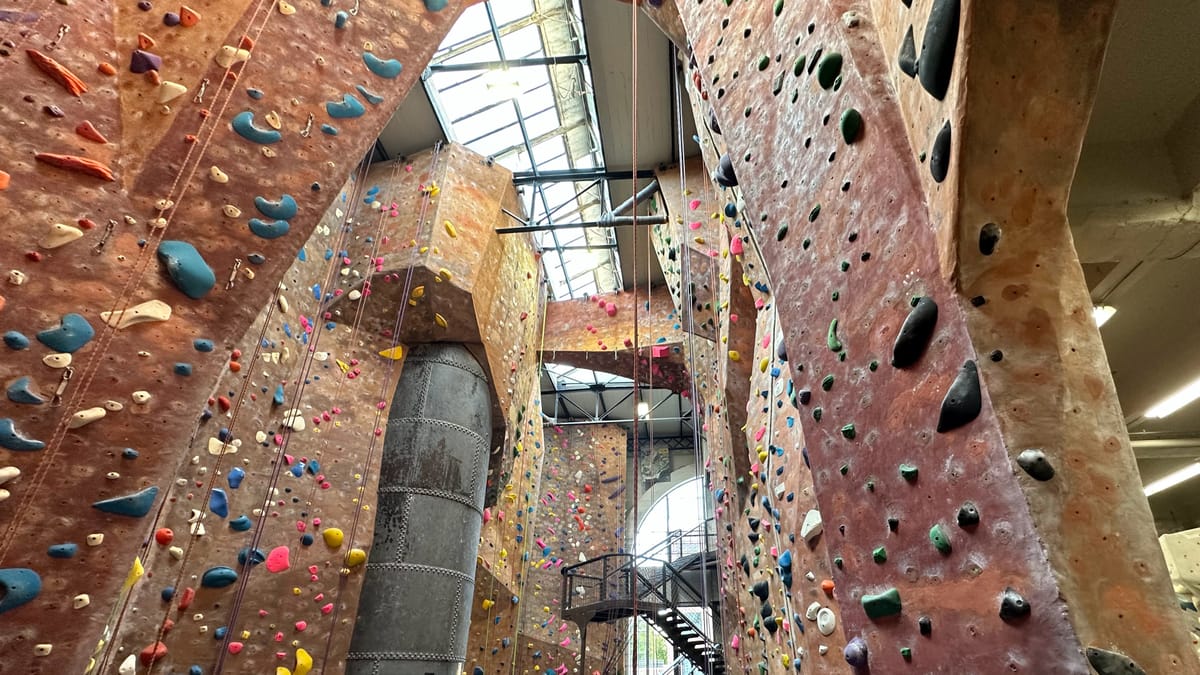

After too-long a hiatus, I resumed climbing last year. I was incredibly lucky to meet an amazing climber at a Queer Crush meet-up in Oakland, and we've been climbing as our nomadic schedules allow.

We both value intention in climbing, and I've been exploring how deeply detailed I can find intention. Below is a list of the skills I've discovered that have helped me improve as a climber.

Partners

Who I climb with has a huge impact on my session. I mentioned meeting an amazing climber last year, but my life-partner has recently started climbing. Sandwiched between these two, I have a wonderful, supportive, enthusiastic climbing experience.

Before these two, I had several wonderful (and sometimes less wonderful) climbing partners, all of whom contributed to the understanding of climbing I have today.

Headspace

Pre-climb

Unlike other sports I enjoy (running, cycling, swimming), climbing requires me to be fully present, from the tips of my toes to the tips of my fingers, and how my head is oriented. Whilst I prefer to go into the other sports with a clean headspace, I can get away with zoning out, or relying on the repetitive nature to tune me in.

With climbing, I need to be in a clean headspace before I leave for the Kletterhalle: a 3m breathing exercise before I leave is enough.

While on a route

Sometimes, I'll be in flow-state, sending a hard route, when someone will fall next to me, and my bubble of concentration bursts. Someone else will call for a 'take' and I'll remember how tired my forearms are, and the bubble will burst. A sign that I'm fatiguing is that I won't be able to maintain my situational awareness, apart from the situation, and I'll be pulled into their situation.

In the same way taking a few minutes before leaving for a session helps, taking a moment before a climb can also help. How am I feeling? Who else is on the wall near me? How are they climbing? Do we overlap?

Fueling

Climbing - indoor, anyway - is an interval sport, defined by periods of high intensity (when climbing), and low intensity (belaying, watching). Determining how best to fuel for this is important: I like a snack mid-session, it massively improves the feeling of sends seven and onwards.

Movement

Mass distribution basics

Climbing is a sport often defined not by strength, but by incredible efficiency. Understanding about the mechanics of leavers, for example, when applied to foot (and really toe) position, can save huge amounts of energy in the arms. Moving in a series of small, easy moves, instead of one large move, saves a lot of energy across the organism. Converting an understanding of efficient movement to muscle memory, so that when fatigued, I always place my toe on a hold, always keep my hips close to the wall, will massively improve my climbing experience, both when fresh and fatigued.

Movement types

In addition to how to take mechanical advantage of my body, learning fundamental movement types, such as foot swaps, step-throughs, flagging, and so on, will improve efficiency. Instead of inventing each move each time I need it, I can recognise a sequence of movement types ahead of time, and connect them together in my mental shorthand when reading a route.

Breathing

When I watch an experienced yogi, I notice how their movement and their breath are in sync. The harder I climb, the more important I find it to move in sync with my breath: breath in before a hard move, hard breath out as I make the move, repeat. I find the synchronisation between body and experience helps maintain flow state in challenging situations.

Reading a route

Climbers talk about reading a route, but I think it breaks down into three tasks:

- Selecting a route: beyond grading, which between internal grade snobbery, and human inconsistency, being able to quickly look at a route and select one of effort appropriate to my energy level is important. Too easy, and it'll feel like a ladder, too hard and it'll be a poor investment of my energy as I struggle up it.

- Ascent planning: once I've selected a route, I try and do what a lot of climbers do: I'll stand at the bottom, and move my hands in sequence with the holds as I look at them. I'm visualising my ascent, attempting to move it to a pre-planned state for efficiency execution. The goal here is that when my plan fails, I'm mentally ready to create a new plan, while hanging off the wall.

- Ascent execution: plans so rarely survive contact with implementation: what I thought was a jug, nay, a bucket, might turn out to be less good than I thought. I might mis-read the angle of the wall, and its impact on the effectiveness of a hold.

Being ready with a library of movement types and efficient mass distribution skills allows me to revise my ascent with minimal fuss, and a clean mind and well-fuelled system allows me to see the solutions, and have the energy to implement them.

Supportive speech

A common piece of encouragement from the ground is 'come on! come on!' But does this work for me? What do I like to hear as encouragement? As the product of toxic masculinity (at least in sports), I don't actually know what I like: I do know I don't like the concept of being angry to execute. What does my partner like? What spurs them on, and what drags them down?

Recognising fatigue

Both my own, and my partner's fatigue are important to recognise. Not in the broad strokes of looking haggard, but in the subtleties of our movement. Acting on that thought of "I'm normally much more elegant... ah, but that was my eighth climb, so..." means more sends later.

The same applies to your partner: are they dragging their feet where they don't usually? How's their hand placement? Being able to say 'how are you feeling, because you're looking tired' without judgement is valuable.

Skin, shoe and equipment care

Generally, two parts of you make contact with the route: your feet, through your shoes, and your skin, through your fingers (and sometimes elbows and knees).

Skin care

As I've climbed longer and harder, I've noticed that I need to listen not just to my muscles and my mind, but also my skin for when to stop climbing for the day. Increases in humidity can cause flappers much faster than I'm used to. Paying attention to the sensation in my skin means I can climb more, even if not that day, as I'm not waiting for my skin to heal.

Shoe care

The rubber on shoes has a very large amount of friction, until it gets covered in chalk. Paying attention to this - storing my chalk bag in a sealable plastic bag - makes for much better climbing. Taking the time to brush chalk off shoes if I notice their chalky makes for much better climbing. Letting shoes air between climbs makes it much better for everyone.

Equipment care and choice

Our climbing and belay equipment are literally life-saving devices. Making sure they're in good condition leads to confidence on a route for both you and your partner.

Making sure you have equipment appropriate to your skill level and style is also appropriate. I want very aggressive shoes, because they look cool, but there's no point having them if I can't complete a climb in them.

Chalk/moral support powder is another one: some people prefer liquid chalk (almost no-one), and others preferred powdered... and then which powder? Finding out what works for your sweat/skin/humidity combination is incredibly valuable.